As you write more complex types, you’ll notice your code growing.

You might also start seeing code duplication…

When you need to reuse TypeScript code, what do you do? How can you keep your code DRY? How do you reduce the boilerplate code?

There are a few main concepts in Typescript that help you accomplish that goal of reducing boilerplate and reusing more code.

sponsor

Tu producto o servicio podría estar aquí

We’ll be specifically be covering Generics and Mapped Types

Both concepts can be a bit scary at first, mostly because of a knowledge gap that creates a wall and makes the code un-readable at first.

Generics are a way to create, in the type world, a similar functionality that functions offer.

Mapped Types are a way to derive and reshape types into new ones.

But, before diving into these new concepts, you need to build up your knowledge with the key features that enable the power of Generics and Mapped Types.

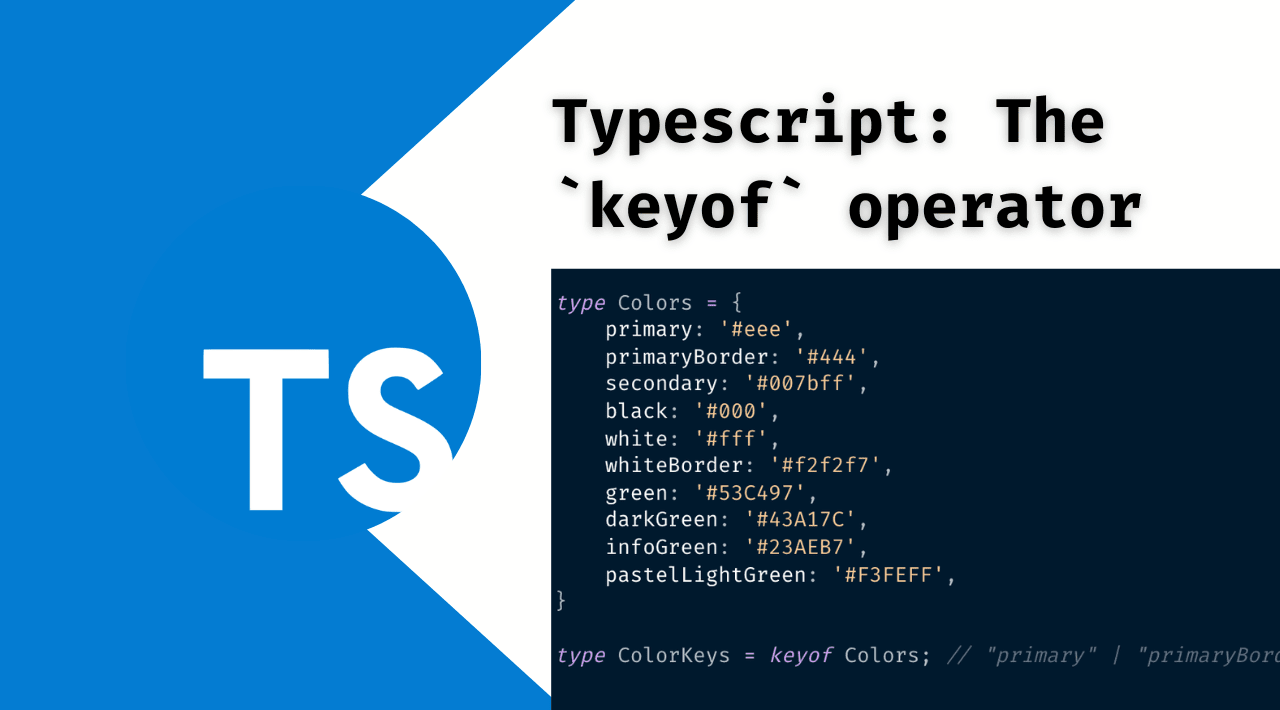

The keyof operator

keyof is Typescript’s answer to the JavaScript’s Object.keys operator.

Object.keys returns a list of the properties (the keys) of an object. keyof do something similar but in the typed world only. It will return a literal union type listing the “properties” of an object-like type.

This operator is the base building block for advanced typing like mapped and conditional types.

type Colors = {

primary: '#eee',

primaryBorder: '#444',

secondary: '#007bff',

black: '#000',

white: '#fff',

whiteBorder: '#f2f2f7',

green: '#53C497',

darkGreen: '#43A17C',

infoGreen: '#23AEB7',

pastelLightGreen: '#F3FEFF',

}

type ColorKeys = keyof Colors; // "primary" | "primaryBorder" | "secondary" ....

function SomeComponent({ color }: { color: ColorKeys }) {

return "Something"

}

SomeComponent({ color: "WhateverColor"})

SomeComponent({ color: "primary"})

The previous code sample is an snippet from a real webapp, the Colors type describes a set of colors that can be used across the application.

The keyof operator is apply to the Colors type to retrieve a literal union of all the possible colors.

The union is then used to type the props of SomeComponent allowing the color argument to be one of the colors defined in the type.

keyof as constraint

The keyof operator can also be used to apply constraints to a generic.

For this example will be enough to know that a Generic behaves similar to a function argument and that the Generic type can have a type or constraint.

function getObjectProps<Obj, Key extends keyof Obj>(obj: Obj, key: Key): Obj[Key] {

return obj[key]

}

The Generics code here is that weird angle brackets section <Obj, Key extends keyof Obj>. That section defines that this function receive two “type parameters” that obey certain rules.

Then, the function declares that the arguments are of the type of that “type parameters” and it will return a type derived from the generic values as Obj[Key]

Let’s disect the generic portion of the above function definition

Objis the name used to identify this Generic parameter. Usually people use single letters to identify the generic, but IMHO is clear to use a better name like variables. The intention here is to accept any object.The second generic parameter is

Key extends keyof Obj. Here tehextendskeyword is used as a constraint, can be read as “Key is of …” meaning that theKeygeneric can only be a value found inkeyof Obj.keyof Objis as mentioned before a union of string literals from the properties ofObjandObjis the first generic paramter. So in Typescript you can reference the previous generic directly.

sponsor

Tu producto o servicio podría estar aquí

So, what all of that means?. It means that the function arguments of getObjectProps will accept any object inside the obj argument, but they key argument can only be a string literal that exists as a property of obj

const User = {

name: 'Matias',

site: 'matiashernandez.dev',

location: {

country: 'Chile',

city: 'Talca'

}

}

const email = getObjectProps(User, 'email') //Argument of type '"email"' is not assignable to parameter of type '"name" | "site" | "location"'.

const loc = getObjectProps(User,'location')

Other type of constraint that you can write using the keyof operator is to restrict the return type of a function.

function objectKeys<Obj extends Record<string, unknown>>(obj: Obj): (keyof Obj)[] {

return Object.keys(obj) as (keyof Obj)[];

}

The above example can be read as objectKeys accepts a obj arguments that has to be of type Record<string, unknown> and will return an array of all of the properties of that obj.

keyof and template literals.

You can also use keyof to construct complex template literals like the following example.

type State = {

modalOpen: boolean;

confirmationDone: boolean;

}

type SetActions = `set${keyof State}` // setModalOpen | setConfirmationDone

This will generate a union of literal strings based on the State properties concatenating the property name with the set word.

There you go, the keyof operator can be small but is an important piece in the big scheme that unlocks powerful operations when used in the right place.

The extends keyword

This keyword is very confused at first time, this keyword is used in a few differnt places holding different meaning.

The first usage of extends is around interface inheritance, this is allowing you to create new interfaces that inherit the behavior of a previous one, in other words, extending the base interface/class

Interfaces have two main purposes:

- Create the contract that a class must implement

- Perform type declaration.

interface User {

firstName: string;

lastName: string;

email: string;

}

interface StaffUser extends User {

roles: Array<Role>

}

In this example, the first interface User just describe a type that have a few properties that represents a general user of a certain application. The second interface named StaffUser represents a user that is part of the organization and therefore have a set of roles. But this user also have firstName, lastName and email and you don’t want to write that over and over again right?. But more important, what if the general User entity change? How can you be sure that the change is represented everywhere else?.

That’s why the StaffUser is written with the extends keyword saying that this interface have all of the properties of the User interface, plus, the ones defined by itself.

This usage of extends can be used to inherit from multiple interfaces at same time by just using a comma separated names of the base interfaces.

interface StaffUser extends User, RoleUser {

}

Other usage of the extends keyword is to narrow the scope of a generic to make it more useful.

export type QueryFunction<

T = unknown,

TQueryKey extends QueryKey = QueryKey,

> = (context: QueryFunctionContext<TQueryKey>) => T | Promise<T>

In the above example (from a real world implementation of tanstack-query) a new type is defined, named as QueryFunction. This type accepts two generic values,T and TQueryKey.

The extends keyword here is used to constraint the possible values of the TQueryKey generic to be of the type QueryKey defined in other place of the source code. This can be read as TQueryKey has to be of type QueryKey.

This usage of extends narrowing down or constraining the type of a generic is the corner stone to be able to implement conditional types since the extends will be used as condition to check if a generic is or not of a certain type.

The never keyword.

never is a type “value” that represents something that will never occur. This is very handy to implement differnt types as conditionals and discriminated unions.

A simple example can be to define the type of a set of function arguments, where some of those arguments are dependent.

type CardWithDescription = {

title?: never;

footer?: never;

description: string;

}

type CardWithoutDescription = {

title: string;

footer: string;

description?: never;

}

type CardProps = CardWithDescription | CardWithoutDescription

function Card(props: CardProps) {

return null

}

import React from 'react';

function App() {

return (

<>

<Card title="Title" footer='footer' />

<Card description='description' />

<Card description='description' title="title" footer="footer" /> // ERROR

</>

)

}

A React component that can accept some props is a good example, in the above code you can see that there three types defined.

CardWithDescriptiondefines a type that can have adescriptionproperty asstringbut withtitleandfooterasnever, meaning that they cannot be defined or used.CardWithoutDescription: This is the opposite type, wheredescriptioncannot be used buttitleandfooterare mandatory.CardPropsdefines a union of the previous two to then be used to type the props of theCardcomponent.

With this setup the Card component can only be used with description and no footer and no title or vice versa. If for some reason you try to use the three props together you’ll get the following error:

Type '{ description: string; title: string; footer: string; }' is not assignable to type 'IntrinsicAttributes & CardProps'.

Type '{ description: string; title: string; footer: string; }' is not assignable to type 'CardWithoutDescription'.

Types of property 'description' are incompatible.

Type 'string' is not assignable to type 'undefined'.

Generics

Generics are the typescript answer to be able to build well-defined and consistent APIs, that are also reusable. In any programming language you have ways to implement the DRY principle, typescript is not different.

With Generics you can build dynamic and reusable pieces of code that somehow resemble a JavaScript function.

Maybe you already encounter the usage of Generics or maybe not, so let’s see an example of generic in the wild.

type IsArray<T> = T extends any[] ? true : false;

type res1 = IsArray<number[]>;

type res2 = IsArray<["a", "b", "c"]>;

type res3 = IsArray<"this is not an array">

The example shows a type named isArray that receives a Generic “parameter” named T and uses that to do some conditional “calculation” to return true or false.

This example can give you a hint: Generics are “like” function parameters of the typed world.

For “convention,” the name of the Generics is one capital letter, but that is not required. You can pass any name to it.

type IsArray<Array> = Array extends any[] ? true : false;

To be able to use generics, you need to follow the syntax, this is, those angle brackets.

When Typescript sees those brackets, it understands that inside of it there are type variables defined. You can pass whatever number of generics you need.

Then, this type “parameters” can be used inside the type definition: the right side of it.

Generics can be used all over the place in typescript, for example, to create an interface that changes based on the generics used.

interface UserInfo<X,Y> {

name: X;

rol: Y;

}

const user: UserInfo<string, number> = {

name: "User 1",

rol: 1

}

const user2: UserInfo<string, string> = {

name: "User 2",

role: "admin"

}

In the example above, the interface UserInfo has two properties that depend on the generics used.

- name: will be of type X

- role: will be of type Y

So when you do UserInfo<string, string>, you have that both properties will be strings.

Generics can be found in almost every typescript codebase since are the basic way to create reusable chunks of code and also the basic tool of library authors to create a flexible API.

Conclusion

Mapped types and generics are powerful tools for any TypeScript developer.

With a good understanding of the key features of typescript, such as the keyof operator, the extends keyword, the never keyword, and generics, you can unlock the full potential of TypeScript and write complex solutions for complex data shapes.

With these features, you can create and reuse code, narrow down types, and create custom types, all while ensuring that your code remains DRY.

For more curated TypeScript content, check out our TypeScript landing page!

sponsor

Tu producto o servicio podría estar aquí

😃 Thanks for reading!

Did you like the content? Found more content like this by joining to the Newsletter or following me on Twitter